"Invoking the Wild," by Associate Principal Nancy Seaton, has been published in Landscape Architecture Frontier’s February 2021 Issue.

Wildness is perhaps best appreciated in contrast to the designed urbanity of our cities, a counterpoint to the smooth neutrality of concrete and glass with which they are clad. The urban environment is full of such wildness, as uncultivated plants take root in the interstitial fabric—along roadsides and chain-link fences, between cracks of pavement, and within vacant lots, rubble dumps and highway medians. While many perceive these spontaneous urban plants (SUP) as a sign of dereliction or entropy, others marvel at the intrepid species’ ability to thrive in the unlikely places where they are found, however small the moment of botanical revolt.

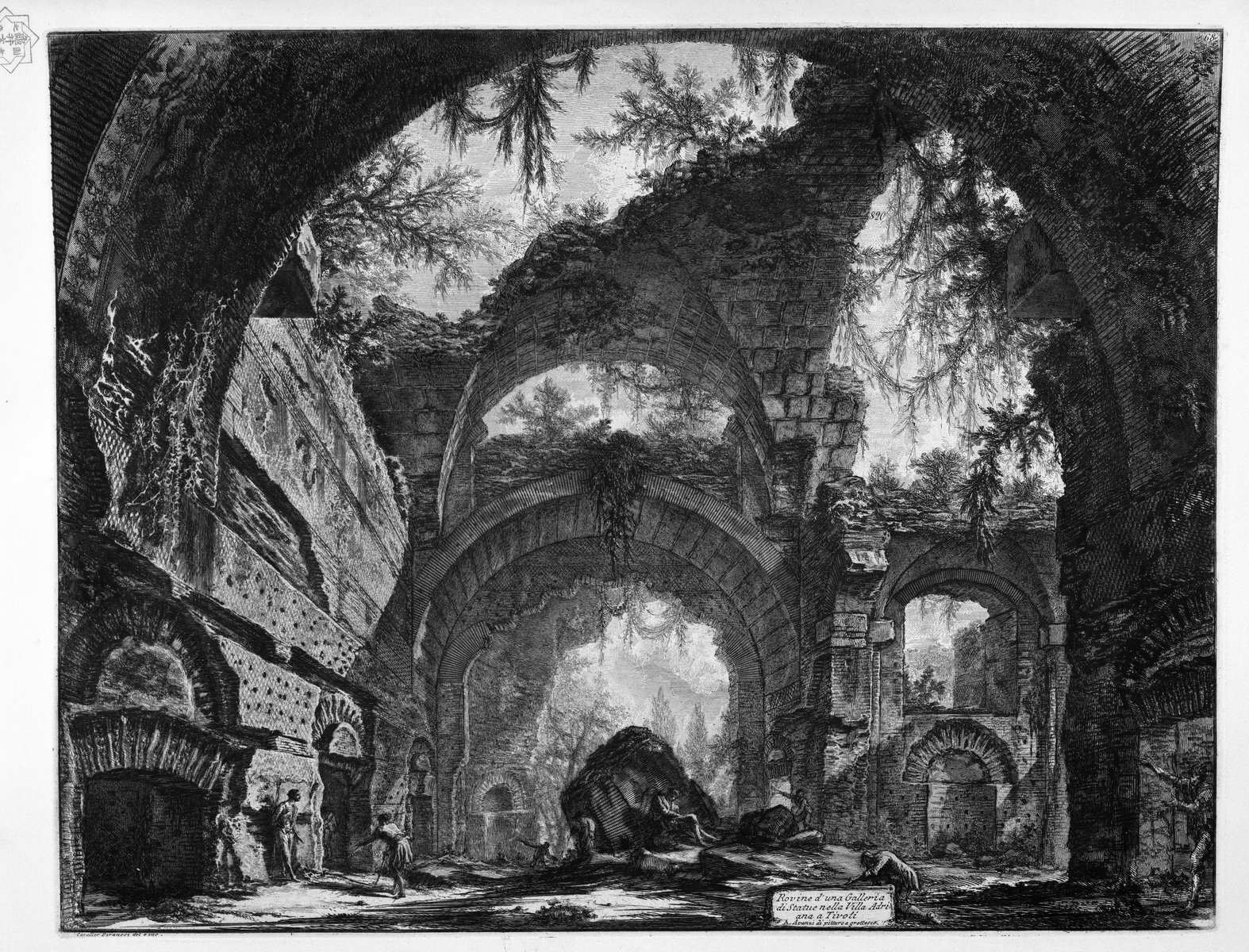

The fascination with wild vegetation taking hold of architectural remnants is hardly a new, post-industrial phenomenon1 and can be seen in Piranesi’s 18th century veduta of Roman antiquities. These prints showcased the poetic nature of ruins that served as memento mori—a commentary on the transience of human life and civilizations. While the forms of sublime, often fantastical, architecture and feats of engineering were at the core of these views, they also speak to the parallel interest of documenting plant life encountered by naturalists in European and North American growing within cities. The popularity of “discovering” the ruins of Rome was still strong a century after Piranesi produced his studies, and a tourist guide to the 420 wild plants that could be found growing on the Colosseum of Rome was printed, which included the properties of each species, practical uses and references in literature and mythology.

Botanists continued to catalog and refine floras, throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with an emphasis on territories that had not been documented, or that were perceived as pristine. It was not until the 1970s that urban ecology was recognized as its own field of study with scientists identifying a cosmopolitan flora that was common between cities around the globe. In the United States, institutions became increasingly interested in documenting the species that composed this group of plants. As early as 1974, Harvard University (Massachusetts) published an issue of Arnoldia dedicated to field identification of what they called wild plants in the city, significantly not calling them weeds.

In New York City, two of the botanic gardens have sponsored long-term research projects about the city’s flora. Brooklyn Botanic Garden initiated a study of all plants within a fifty-mile radius of New York City in 1990, New York Metropolitan Flora Project (NYMF). The work significantly increased data of the city’s flora, filling herbaria with new specimens that documented the shrinking populations of indigenous species and the expansion of non-native plants, represented in a series of comparative maps. In 2018, The New York Botanical Garden established the New York City Eco-flora Program, which seeks to engage citizen scientists with the preservation and protection of native plants, while also supplementing current data to inform policy decisions. The 2018 publication, The State of the City’s Plants projects a multivalent strategy for plant conservation in New York City that includes volunteer participation, alongside the work of NYBG researchers.

Both projects are embedded in a decades-old, expansive conversation about the detrimental effects of invasive and non-native plants, but plants have no volition—humans have created the conditions in which species thrive or decline and continue to make them.

What happens if one questions the assumption that the urban flora is simply “bad” or valueless?

This is not just a provocation—more than half of the world is urbanized; the ability of cities to support historic genera falters as the biotic and abiotic systems are irrevocably altered, becoming novel ecosystems. Peter Del Tredici’s Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide emphasizes the significant role this group of plants plays in contemporary urban ecology, not promoting them as a replacement of natives, but detailing contemporary realities and scientific trends for a broad public readership.

EXPLORATIONS

Situated within this continuum of discourse, Future Green Studio launched what would become a series of projects around the theme of wild plants found in the urban environment or SUP (spontaneous urban plants). Begun in 2011, the first phase of the project highlighted SUP along a section of 3rd Street sidewalk near the office. Yellow circles were painted around SUP to draw attention to the ubiquitous, but generally overlooked plants. This phase included office walks, recorded observations, and identification of the commonly found species. One of the intentions of framing these plants was to invite neighborhood residents to look more closely—to start actively noticing the plants that they cohabitate the city with—to upend the perception of weeds as nuisance by subtly changing the context. In next steps, the office initiated an art and research project, and engaged a broader audience to interact with their local environments through the app, Instagram #spontanenousurbanplants. The Instagram app allowed people to participate in a new wave of botanical exploration, searching out typical and unusual species in all corners of the city, creating a spectacle of weeds through artful photography.

The office participated in an additional series of walks (2013-2016), some full-day explorations, others lunch-time rambles around Red Hook, Brooklyn a former industrial, waterfront neighborhood where the office is situated. FGS began to compile plant profiles and charts of species grounded in field observations and research into cultural uses and nativity. The appearance of wild vegetation can be an asset, if left to grow in the interstices in between places; mats of vegetation in the sidewalk and in tree pits contribute to erosion control—slowing storm water, reducing the cumulative impact of major storm events; uncultivated trees offer shade to otherwise hot, paved surfaces, lowering the urban heat island effect. In describing the SUP project, founding principal, David Seiter states the following, “[w]hat’s remarkable about all spontaneous urban plants is the fact that they require no human assistance to assert and maintain themselves in extreme, often volatile urban conditions, while providing the same ecologically performative benefits of traditional landscape plants and street trees. Rather than seek to discard and eradicate them, we now have an opportunity to harness their benefits and tell their histories.”

WILD WORKS

Inspired by the plant adaptations that allow urban flora to survive in a variety of harsh habitats, Future Green Studio sees opportunities rather than limitations in the extreme environmental conditions found in urban landscapes. An early project in the office remains a foundational one: 345 Meatpacking, Manhattan, NY, built in 2013. The historic loading canopies of the neighborhood along with the nearby High Line provided precedents for the creation of a densely entrance marquee at the residential building on 14th Street. The constructed landscape has the appearance of one that spontaneously erupted along the façade, bearing the wild demeanor and volume that any number of SUP sites exhibit. The extremely shallow growing media, between six and twenty inches, supports clusters of staghorn sumacs, an herbaceous mix, and cascading plants that spill through the openings and over the edges of the concrete canopy. This project embodies the spirit of SUP in many ways, as the awning is not a site where plants are typically seen, passersby “find” the suspended landscape by accident. Whimsical and idiosyncratic, 345 Meatpacking has introduced many to the office’s work, along with the façade planting at 41 Bond Street and 22 Bond Street.

Most of the firm’s design work has been in cities, on structure, rooftops and bulkheads, with weight and program restrictions. To bring a sense of identity to sites that have long been stripped of vegetation, native soils, topography, hydrology, and geology—paved over and built upon—Future Green looks to the natural history of each site. Plant palettes are assembled to provide maximum volume for the often-limited depth of growing media, to create landscapes that provide a wild beauty, full of contrasting textures and seasonal markers, as in our work at Empire Stores in DUMBO, Brooklyn, with over 50,000 square feet of planted green roof, completed in 2016.

While we continue to question the perception and value of SUP, we also embrace the native plants and ecologies of project sites for inspiration, using specific habitats created by the built environment to inform species selection. The office draws on their lessons of plant adaptation learned through observing uncultivated plants thriving despite exposed conditions. Not all the SUP encountered by the office were invasive species; many plants discovered on walks were native, seaside plants able to withstand drought, heat, lean soils, and salt spray. Species are selected for their ability to tolerate the proposed habitats and are often drawn from local plant communities, such as oak barrens and shrublands. This strategy has been employed on several recent projects, including Georgia Power, in Atlanta (designed, 2019), which incorporated plants from the Piedmont and the coastal plain. Another current project, in New York is in the site of the former St. John’s Terminal, in Manhattan. Here, the architectural team has created a sectional cut through the former industrial rail, which will soon support a cultivated ecology of native plants. The planting is designed to appear effortless, naturalistic, wild—but is a highly engineered orchestration. The palette was assembled considering field-observations of urban-adapted species, historic ecologies detailed in Manahatta, and plant lists issued by the Natural Resources Group of the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. Many of the places FGS designs are incorporated into new construction; composing future ecologies for spaces that would otherwise be inert, for conditions that have never existed. While it is neither possible nor the goal to reproduce the complexity of an extant, native ecology it is the intention to evoke scenes of local landscapes, to situate places within specific contexts.

There is much work to be done in quantifying the benefit of green roofs and urban green space in general, to understand which plants are performing well, and are best able to support a rich array pollinators, insects, birds, and other wildlife—which the firm regularly tries to attract; monitoring these sites is high on the list of next steps in the studio’s practice, in partnership with urban ecologists, soil scientists, students, and enthusiastic volunteers. Wildness is an invitation to the unexpected, which embraces vigor and heterogeneity over manicured monocultures, engagement with time, and often, a light hand in control.

Future Green Studio’s investigations into spontaneous urban plants have aspired to engage people with their neighborhood environments—streets, walls, lots, and tree pits—through a series of walks, talks, citizen science participation and the publication of a book, SUP. This work continues to feed planting concepts behind many of the firm’s designed landscapes, which foster a sense of discovery and immersion. The rugged vision of urban wilderness the firm is inspired by does not see uncultivated plant growth as the specter of disinvestment, but as an asset to the performance, health and well-being of its inhabitants, human or otherwise, which demonstrates the ability of the city to support the evolving ecologies of the future. Natural process is not something that happens elsewhere but can be observed in whatever context we may find ourselves; there are no political boundaries or classifications that divide the biotic. Cultivated and uncultivated plants sprouting from all manner of surfaces within our cities serve to remind us of the interconnectedness, adaptability, resilience, and fragility of all life.